THB #93: The Batman (no spoilers)

| March 6, 2022

“Thank you for the days, those endless days, those sacred days you gave me. I’m thinking of the days, I won’t forget a single day…” are words sung in an emotional crescendo near the end of Until The End of the World, a Kinks song sungalong in the middle of the night on the bottom of the planet at what a raft of characters believe is already of the end of civilization as they know it, as Wim Wenders and his co-writers Peter Carey and Solveig Dommartin anticipate.

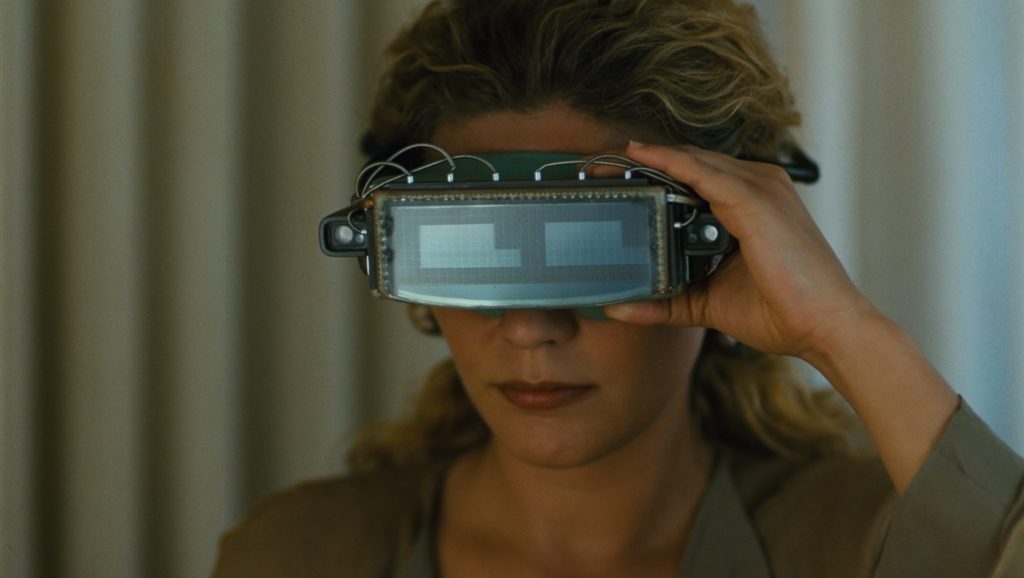

What appears to be a cosmopolitan picaresque moves from moment to moment to momentousness, through the wanderings of one Claire (Solveig Dommartin), from Venice to Paris to Lisbon to Berlin to San Francisco to Japan to China to Moscow to Alice Spring, Australia, fifteen cities across five continents, where finally, in a cavern on native territory, virtual reality-like images are reproduced in a blind woman’s mind. It’s an Odyssey, to be sure, but about more than a journey, including the reunion of an obsessive scientist, Dr. Farber (Max von Sydow) and his peripatetic progeny Sam (William Hurt). For what it’s worth, in German, “farber” can be a dyer of cloth, and there are colors galore in Wenders’ tapestry. (He’s also written that the noirish narrative is “Penelope decides to set out in pursuit of Odysseus.”) The threads include the anticipation of high-definition images, the first seen in a feature film, and Claire’s ex-boyfriend Eugene (Sam Neill), a novelist who narrates and refracts the movie we are seeing as a narrative he is transcribing and transforming.

It’s love stories: “We are criminals that never broke the law,” David Byrne intones in the first of the wall-to-wall stretches of seductive, alternately dreamy and percussive music, and “she was in love with the idea of being in love,” Eugene narrates.

It’s the most melancholy of romantic fairytales. How did the story begin? A satellite began to fall from on high and Claire began to tumble into adventures: “I broke up with my boyfriend, he fucked my best friend, I went to Italy.” And later she marvels at the motivations of her men: “Why are you so good to me? It is your way to punish me?”

But Wenders does not punish Claire. His then-partner Dommartin extends the grace of her physical performance as the trapeze artist in Wings Of Desire: the way she moves! Coiled, tensile at rest, on the balls of her feet as she walks across a frame in a miniskirt patterned like a Buckminster Fuller geodesic design, she provides lithe counterpoint to the lassitude of other characters. She begins as a sybarite in a black Louise Brooks wig with architectural bangs: when she whips it off, a cascade of thick blonde curls erupt and the film is freed, just as in Wenders’ Kings of the Road when the narrative was loosed only by a character has a seriously successful release on a beach, each figure freeing themselves physically to whatever may come next.

Now a lustrous epic masterpiece of effortless science fiction, with giddy film genre borrowings, and futuristic prediction turned period piece, World was first released in a shorn, shattered version of 179 minutes that satisfied no one, especially Wenders. Time is of the essence: set in 1999, shot in 1990-91, released at a compromised, unsatisfying 179 minutes in 1991, Wenders’ dream is only just now released in an integral, near-five-hour walkabout.

And another form of time is of essence: below the sleek, cool, yet warm-to-the-touch surfaces of Wenders’ bold film, his years-in-thought, predicting 1999 in 1990, anticipates 2015 and beyond. “When we finally got to shoot it, the year 2000 was ten years away, but it was still fun to project ourselves into the future of the audiovisual revolution that had just started,” Wenders observes on the Criterion edition. “The word digital was still only known to some technofreaks. Nobody had any idea that everything was going to be digital: images, text, our whole lives.”

The world’s fears of end times come with the descent of an Indian nuclear satellite into the atmosphere, where the United States threatens to detonate it mid-air, which could cause a worldwide electromagnetic pulse, wiping the memory of all the machines. The fear of Y2K had not yet made the news; the personal computer browser was a couple of years from introduction, although World uses “Russian software” like latter-day apps doing the work Google (launched 1997) does now. Autonomous cars ply neon roads of Tokyo. Suicide bombers release propaganda video before killings.

“In the beginning was the word. What would happen if only the image remained in the end!?” someone exclaims. Most disturbingly and most prophetically, characters grow obsessed with images they stare into on handheld devices, images from one’s own dreams as harbingers of mental illness.

But in the end, as Eugene narrates, Claire overcomes her “deep well of narcissism” and there is a delirious moment that should be laughable, but it is instead the perfect place for Claire to celebrate her thirtieth birthday, which I’ll hint at only as an angel’s flight.

A single day after a single day, after nearly twenty-five years of sacred days before Until the End of the World: a great and poetic and caring film has arrived at last.

-30-

May 1, 2022

"Netflix, the great disrupter whose algorithms and direct-to-consumer platform have forced powerful media incumbents to rethink their economic models, now seems to need a big strategy change itself. It got me thinking about the simple idea that my film and TV production company Blumhouse is built on: If you give artists a lot of creative freedom and a little money upfront but a big stake in the movie’s or TV show’s commercial success, more often than not the result will be both commercial (the filmmakers are incentivized to make films that will resonate with audiences) and artistically interesting (creative freedom!). This approach has yielded movies as varied as Get Out (made for $4.5 million, with worldwide box office receipts of more than $250 million), Whiplash (made for $3.3 million, winner of three Academy Awards), The Invisible Man (made for $7 million, earned more than $140 million) and Paranormal Activity (made for $15,000, grossed more than $190 million).From the beginning, the most important strategy I used to persuade artists to work with me was to make radically transparent deals: We usually paid the artists (“participants” in Hollywood lingo) the absolute minimum allowable by union contracts upfront, with the promise of healthy bonuses based on actual box office results—instead of the opaque 'percentage points' that artists are usually offered. Anyone can see box office results immediately, so creators don’t quarrel with the payouts. In fact, when it comes time for an artist to collect a bonus based on box office receipts, I email a video clip of myself dropping the check off at FedEx to the recipient."

Jason Blum Sees Room For "Scrappier" Netflix

| April 30, 2022

"As a critic Gavin was entertaining, wry, questioning, sensitive, perceptive"

Critic-Filmmaker Gavin Millar Was 84; Films Include Cream In My Coffee, Dreamchild

April 29, 2022

| January 24, 2022

DP/30 Audio: Bombshell, Jay Roach

| December 13, 2019

DP/30 Audio: The Last Black Man in San Francisco, Jonathan Majors

| December 4, 2019

DP/30 Audio: The Mustang, Laure de Clermont-Tonnerre

| December 4, 2019

No Responses to “Wim Wenders’ Restored “Until The End of the World” On Blu”